How to Live with Imposter Syndrome

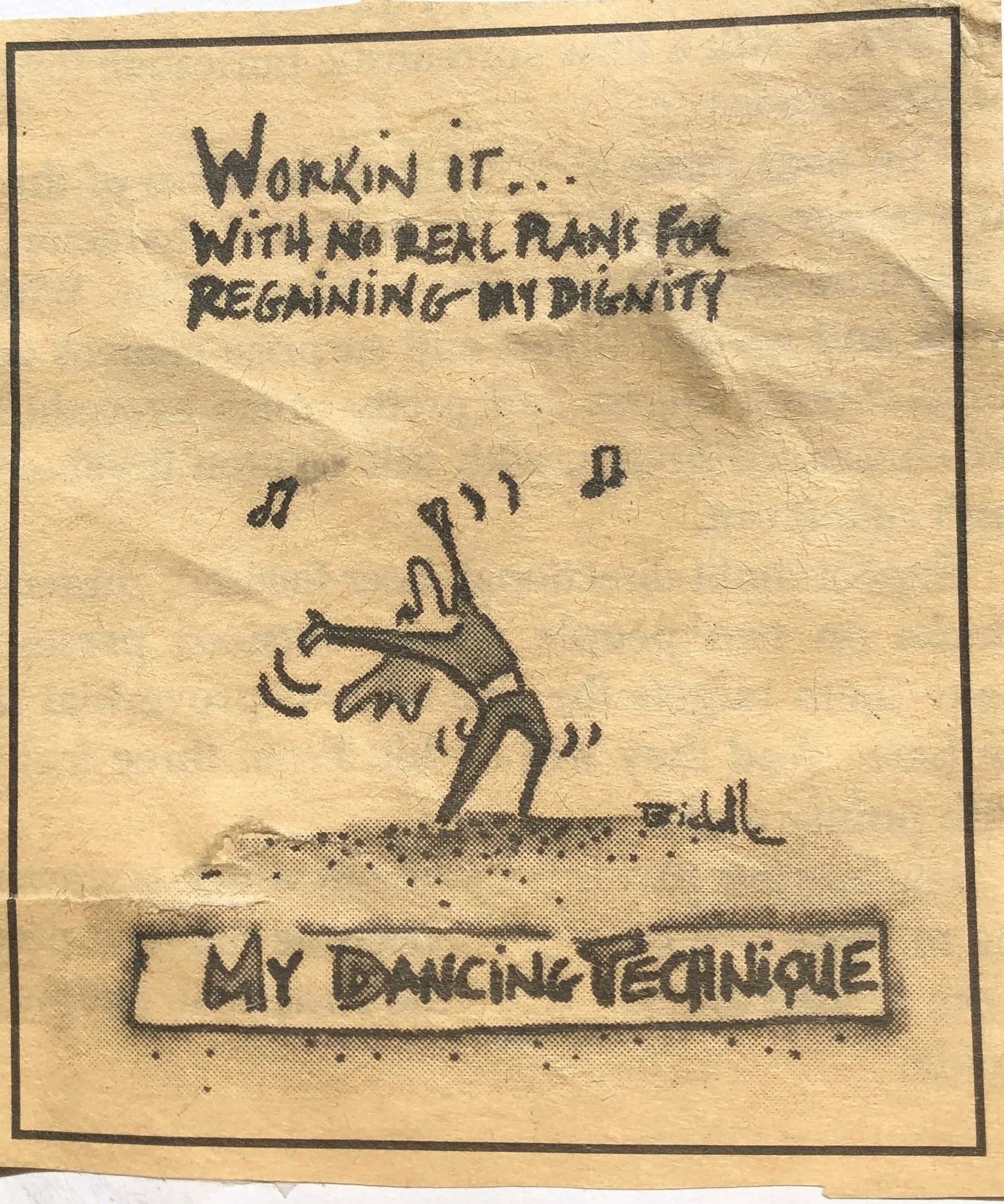

Photo by author of a cartoon she clipped years ago from the Funny Times and taped to the wall she stares at when sitting at her writing desk.

According to Google, Imposter Syndrome is “loosely defined as doubting your abilities and feeling like a fraud. It disproportionately affects high achieving people who find it difficult to accept their accomplishments.” Is this you? Me too. The wordsmith who coined the term probably did so ironically. Though, as a shrink, I would include the syndrome as a legitimate diagnosis in the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It’s real, with real consequences.

Imposter Syndrome functions as a defense against the destructive envy of others. Here’s the misguided logic: if you’re an imposter, there’s nothing to envy, right? Who are these high achieving people disproportionately affected? Women, mostly. Anyway, that’s my experience. Obviously, we need an objective research study.

Imposter Syndrome holds you back from starting a project which will put you in the crosshairs of other people’s envy. Completing a project successfully increases the risk of social attack; a failure confirms you’re a fraud. Over time, if you persist and succeed anyway, Imposter Syndrome makes sure you can’t take pleasure in your accomplishments.

Come on, you say. It’s not that bad. Actually, it is. Here are two tells you can use to self-diagnose. The first is verbal. Do you often put yourself down? For example, do you find yourself saying: If I can do it, a chimp can do it. Be serious. A chimp can’t do what you do. You are either minimizing your achievements to avoid danger— in which case, carry on—or, admit it, you’re fishing. Unfortunately, most people won’t bite and reassure you how wonderful you are. Besides, you wouldn’t believe them if they did. (See how Imposter Syndrome works?) Instead, people will agree with you. Zip your lip. It’s bad enough that you have trouble taking yourself seriously. Don’t encourage others to think less of you.

The second tell is non-verbal. Do you avoid making eye contact? Do you make yourself smaller by walking with rounded shoulders? Do you sit in defensive posture with arms and legs crossed? Nothing is more revealing than movement. (Martha Graham)

Imposter Syndrome is a squelcher and a liar. It’s hard to ignore that sneering voice—Who do you think you are? Somebody else has already done that, and better. Etc.—and put yourself out there. What if you get ridiculed? The primary driver of Imposter Syndrome is fear of public humiliation and group rejection. By whom? Envious people of course.

No matter how accomplished you are, external accolades for your current project only heighten the feeling of impending doom. Outside criticism amplifies your internal critic’s conviction that you’re an imposter. What can you do to shut that voice up? Ignore both criticism and praise. Tell yourself other people’s opinions are a distraction—only yours matters.

But, you cry, I’M the problem! That’s true, and it’s not. Imposter Syndrome is only a small part of you, a little devil perched on one shoulder shouting ugly nothings in your ear. You have a bigger, healthier self, an angel that stubbornly keeps creating. She sits on your other shoulder and whispers all the right things. Listen to that angel.

Work finally begins when the fear of doing nothing exceeds the fear of doing it badly. (Alain de Botton) Expect that nasty little imp to natter dire predictions while you work. Tell it: Thanks for sharing. Keep working. Tell the truth through whichever veil comes to hand—but tell it. Resign yourself to the lifelong sadness that comes from never being satisfied. (Zadie Smith)

Share your work. Then go about your business—perhaps start another project—and think no more about it. Whether or not your baby is well received is out of your control. What other people think is their business, not yours. The experience of creating is what matters, not whether it’s judged by others as “good” or “bad.” The quality of an author’s work is not usually determined until after his death. Dickens got some pretty bad reviews. (Robert Ludlam)

Bottom line: you can’t be a fraud—you can only be you. You are unique, and if that is not fulfilled, then something has been lost. (Martha Graham)

If there is a fraudster, it’s the Imposter Syndrome itself. It’s a negative figment of your imagination, programmed into your neurology. Pat it on its little head: I see you, and then—this is important—do what you want. Put away the expectation that it will go away. It won’t. But you can make it much, much quieter by starving it of your attention and energy. By forgiving yourself for its presence. By continuing to work.